Guest Blogger Sophie Collyer

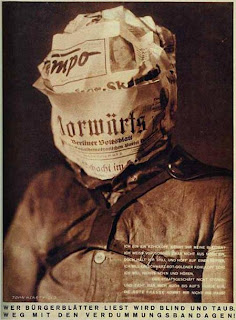

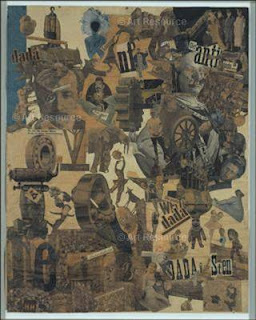

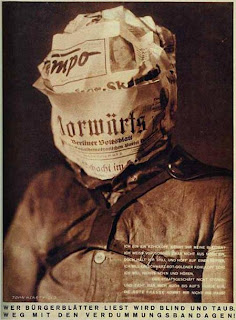

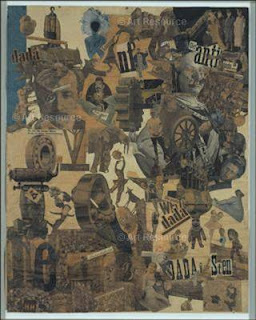

“In the war, things were in terrible turmoil, out of parsimony, I took what I could because we were now an impoverished country. One can even shout with refuse, and this is what I did.” In the wake of World War I, the attitude towards the newspaper in Germany was not as celebratory as that of the Cubists. Artists of Neue Sachlichkeit and Dada condemned the post-war bourgeois newspaper tycoons’ militarism and apathy towards the victims and veterans of the War. However, they could not escape the ever presence of the newspaper torn up on street corners and hung neatly in cafes—they lived in a verbal environment. Newspapers had a daily life. They were pertinent at one moment, but outdated the next, tossed away and used for purposes from wrapping meat to collage. Otto Dix in Prague Street depicts a broken veteran on the street with a torn piece of newspaper; both are old news, modern refuse. Dada artists like Hannah Höch and Kurt Schwitters used photomontage and collaged poems as a means to mimic the chaos of modern life, thus brining form to content. Newspapers were the perfect media for this anti-art group whose famed member, Duchamp, declared the end of painting. The German Bauhaus addressed the newspaper as well, mainly in the realm of typography. As opposed to typefaces that tried to exemplify an idea or status, they advocated modern sans-serif fonts of ultimate clarity. Works of this type were banned by National Socialists in 1937 and Neo-classical figural works and classical typefaces became the state mandated standard.

“In the war, things were in terrible turmoil, out of parsimony, I took what I could because we were now an impoverished country. One can even shout with refuse, and this is what I did.”

–Kurt Schwitters